Key Technical Considerations to Ensure Successful and Sustainable Repowering

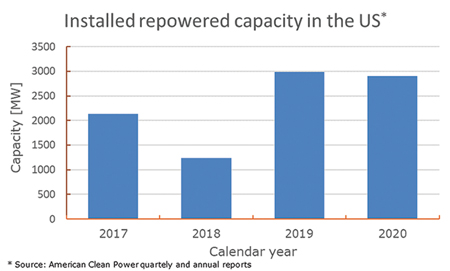

Key Technical Considerations to Ensure Successful and Sustainable RepoweringIn recent years, wind farm repowering has contributed an important fraction of overall US wind farm installations, as developers seek to capitalise on existing infrastructure, proven revenue streams, and tax credit eligibility. Partial repowering, as opposed to full repowering, remains the dominant form in the US market and typically involves reusing the existing foundation and towers, while replacing uptower components with new parts to attain higher performance and financial benefits from the asset. According to the ‘American Clean Power Market Report Fourth Quarter 2020’, partial repowering increased sharply from 2018 to 2019 and remained at roughly 3GW in 2020 (for reference, new US wind installations in 2020 accounted for roughly 17GW).

By Ali Ghorashi, Head of Section, Wind Independent Engineering, DNV, USA